Land Grab at Ile a Vache: Haiti’s Peasants Fight Back

Before Haiti’s Prime Minister declared all of Haiti’s offshore islands to be Zones of Tourism Development and Public Utility, he did not consult with the residents of the islands whose lands would be appropriated. Instead Mr. Laurent Lamothe went to a favorite online magazine in December 2012, to promote his plans. “[W]e have decided to take the tourism development to the island of Ile a Vache, so there we’re going to build an international airport, and then the tourism [infrastructure] to attract investors — we have several investors already…. I think Ile a Vache has great potential, and it doesn’t present the challenges for land title that you might face on the mainland.”

As Ile a Vache, a 20-square mile island off of Haiti’s southern coast was promoted to investors in Qatar, the Dominican Republic, China, the wider Caribbean, the United Kingdom, and United States as being a jewel of the Caribbean and a potential draw for eco-tourists, the residents of the island, mostly small farmers who had cultivated food crops and fished sustainably for more than century, and who occupied homes that had been in their families for many generations, were ignored. The islanders’ requests for meetings with government representatives went unanswered, even while Tourism Minister Stephanie Villedrouin found ample time to report the details of the $230 million project in March 2013, once again, to a magazine.

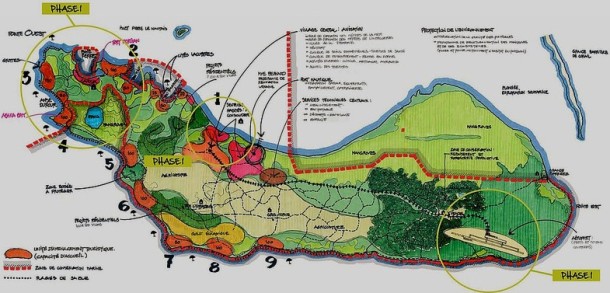

The island’s coasts and beaches, normally used for fishing, would be appropriated for the construction of several resort hotels (about 1500 hotel rooms), plus 2500 villas and bungalows for a “laid-back, low-density eco-tourism-style development, highlighting areas like cultural heritage, agro-tourism…” Initially, an area called Anse Dufour, near the currently touristic Madame Bernard area, would be developed into the “Village of Marie Anne,” with a community center, radio station, restaurants, bars, cafes, arts and craft shops, theater, school to train hotel workers, pirate museum, health clinics and spas, heliport, villas, and bungalows. Later, there would be yet more bungalows, villas, pools, restaurants, floating bars and ports for hydroplanes. There would also be “agricultural infrastructure” to allow wealthy members of the diaspora, adventure travelers, wellness travelers, and honeymooners to learn to farm sustainably as part of their full eco-tourism experience.

By December 2013, after the island’s only forest had been razed, with assistance from theVenezuelan government, to build an airport with a 2.6-km (1.6 mile) runway, the islanders formed the Organization of Ile à Vache Farmers, or KOPI (Konbit òganizasyon peyizan Ilavach), and began to take to the streets in regular protests. The farmers refused to accept the presidential decree that had appropriated as “state assets” all properties and lands in Haiti’s offshore islands and unilaterally annulled all legal property rights that had resulted from either sales, leases, or bequests from individuals retroactively for five years.

On January 6, 2014, the residents issued a one-week ultimatum to the Haitian government, demanding that it immediately stop all plans for “tourist destination, Ile a Vache.” They were especially incensed by the fact that their need for a hospital and high school had been ignored in favor of hotel rooms and golf courses for tourists. Moreover, they noted that local masons, foremen and technicians had been rejected for construction work in favor of people from out of town. One KOPI leader reported that KOPI members had received death threats, but “even our bones will not leave Ile à Vache.”

The Minister of Tourism did visit Ile a Vache on January 16, 2014, not for a discussion but a presentation that disappointed the residents. The residents complained that Mrs. Villedrouin had merely presented them a slide show, when they had expected to examine detailed plans of the tourism project and participate in an extensive discussion of these plans.

The islanders then undertook a new series of protests in which they blocked the roads to paralyze all business activity and construction work on the island. “Ile a Vache is not for sale, not in bulk not in retail,” they chanted. Soon a group of paramilitaries appeared, who began to attack the people in advance of their protests. On the evening of February 8, 2014, for example, police beat up Charles Laguerre, Bertin Similien, Lethe Feguens, and Maxo Bell and forced them to remove the barricades they had erected for their protest; they also beat up a young woman, Rosena Masena, merely for walking in the area of Madame Bernard.

The protests have caused several of the companies for the tourism-development project to leave the island. On the other hand, the campaign to persecute the residents, especially the KOPI leaders has gone into full swing. On Thursday February 20, 2014 over 100 heavily-armed police from the Motorized Intervention Brigade (BIM) invaded a school and destroyed several houses. The following day, a government delegation inaugurated a new community center, restaurant and radio station even as people protested and KOPI’s Vice President (a well-known policeman on the island) Jean Matulnès Lamy was arrested.

On Tuesday February 25, 2014, despite a heavy rain, a spontaneous protest broke out when the islanders learned that Matulnès Lamy had been taken to the national penitentiary without being allowed to see a judge. A group of BIM policemen arrived at the protest, along with the local interim governor Fritz Cesar, who singled out the KOPI members for arrest. Live ammunition was fired into the crowd to break up the protest; two people were arrested and 12 were injured.

Residents are outraged by the violence that the government has brought to a bucolic agricultural island that had traditionally needed only two policemen. Children can no longer go to school because of the invasion of their school by heavily-armed police. KOPI members have gone underground and say they are being called “bandits” and accused of poisoning people’s minds.

Seventeen Haitian organizations have signed a communique to demand the release of Jean Matulnès Lamy, and pledged solidarity with the Ile à Vache residents. “We, the signatory organizations bring our solidarity to the struggle of the people of Ile a Vache to stop the island from being turned into a zone for tourism, and we denounce the arrest and imprisonment [without trial] of Jean Matulnès Lamy for having supported the mobilization of the people of the island. We denounce the attacks and other arrests by police to intimidate the population. We believe that these actions against the Ile a Vache population fit in with the logic of macoute power, at the service of the international, that does not respect the principle of the right to self preservation, which is a fundamental democratic principle.”

Senate Committee for Justice and Security Chairman, Pierre Francky Exius has qualified the arrest of Mr. Jean Matulnès Lamy as being politically motivated. Senator Exius announced on February 27, 2014 that he will call on Justice Minister Jean-Renel Sanon and the Chief of Police to discuss the Ile à Vache situation.

As Haitian businessman Antoine Izmery remarked in 1993, during a similar administration when Haiti was run by a US-controlled military junta: “This country is so corrupt that the Americans do not have to do the corruption. They let you steal your own country, just giving you a little protection.” Haitian culture and agriculture are being dismantled, not by foreign interests this time, but by corrupt Haitians, with a nod and a wink from their foreign handlers.

The people of Ile a Vache do not recognize the May 10, 2013 government decree that wants to divest them of their lands and declare the entire island a zone of public utility. KOPI President Marc Lainé Donald (Jinal) said: “This is a lousy decree. This project reflects a macabre plan, a rat trap, a collective suicide, that aims to drive all the residents from the island. It is a cultural genocide that puts everyone in the island’s storm and dispossesses people of their lands. No one has the right to build on the island any more. If Ile à Vache is a hidden treasure, its people should enjoy it and get integrated into the proposed developments. We are craftsmen who have worked to beautify this corner of paradise that is so coveted by Lamothe’s administration.”

Ile a Vache residents call on people everywhere, especially Haitians on the mainland and the diaspora, to support their struggle. They caution everyone to remember the proverb: “When chicken passes by and sees turkey being feathered, chicken should check if it is wet.”

Editor’s Notes: For frequent updates on this story, click here. Photographs two, three, four, six, eight, ten, twelve, fourteen and fifteen by Marie Chantalle. Photographs one, five, seven, nine, eleven and thirteen, and radio reporting in Kreyol by Radyo VKM, Vwa Klodi Mizo.

Before Haiti’s Prime Minister declared all of Haiti’s offshore islands to be Zones of Tourism Development and Public Utility, he did not consult with the residents of the islands whose lands would be appropriated. Instead Mr. Laurent Lamothe went to a favorite online magazine in December 2012, to promote his plans. “[W]e have decided to take the tourism development to the island of Ile a Vache, so there we’re going to build an international airport, and then the tourism [infrastructure] to attract investors — we have several investors already…. I think Ile a Vache has great potential, and it doesn’t present the challenges for land title that you might face on the mainland.”

As Ile a Vache, a 20-square mile island off of Haiti’s southern coast was promoted to investors in Qatar, the Dominican Republic, China, the wider Caribbean, the United Kingdom, and United States as being a jewel of the Caribbean and a potential draw for eco-tourists, the residents of the island, mostly small farmers who had cultivated food crops and fished sustainably for more than century, and who occupied homes that had been in their families for many generations, were ignored. The islanders’ requests for meetings with government representatives went unanswered, even while Tourism Minister Stephanie Villedrouin found ample time to report the details of the $230 million project in March 2013, once again, to a magazine.

The island’s coasts and beaches, normally used for fishing, would be appropriated for the construction of several resort hotels (about 1500 hotel rooms), plus 2500 villas and bungalows for a “laid-back, low-density eco-tourism-style development, highlighting areas like cultural heritage, agro-tourism…” Initially, an area called Anse Dufour, near the currently touristic Madame Bernard area, would be developed into the “Village of Marie Anne,” with a community center, radio station, restaurants, bars, cafes, arts and craft shops, theater, school to train hotel workers, pirate museum, health clinics and spas, heliport, villas, and bungalows. Later, there would be yet more bungalows, villas, pools, restaurants, floating bars and ports for hydroplanes. There would also be “agricultural infrastructure” to allow wealthy members of the diaspora, adventure travelers, wellness travelers, and honeymooners to learn to farm sustainably as part of their full eco-tourism experience.

By December 2013, after the island’s only forest had been razed, with assistance from theVenezuelan government, to build an airport with a 2.6-km (1.6 mile) runway, the islanders formed the Organization of Ile à Vache Farmers, or KOPI (Konbit òganizasyon peyizan Ilavach), and began to take to the streets in regular protests. The farmers refused to accept the presidential decree that had appropriated as “state assets” all properties and lands in Haiti’s offshore islands and unilaterally annulled all legal property rights that had resulted from either sales, leases, or bequests from individuals retroactively for five years.

On January 6, 2014, the residents issued a one-week ultimatum to the Haitian government, demanding that it immediately stop all plans for “tourist destination, Ile a Vache.” They were especially incensed by the fact that their need for a hospital and high school had been ignored in favor of hotel rooms and golf courses for tourists. Moreover, they noted that local masons, foremen and technicians had been rejected for construction work in favor of people from out of town. One KOPI leader reported that KOPI members had received death threats, but “even our bones will not leave Ile à Vache.”

The Minister of Tourism did visit Ile a Vache on January 16, 2014, not for a discussion but a presentation that disappointed the residents. The residents complained that Mrs. Villedrouin had merely presented them a slide show, when they had expected to examine detailed plans of the tourism project and participate in an extensive discussion of these plans.

The islanders then undertook a new series of protests in which they blocked the roads to paralyze all business activity and construction work on the island. “Ile a Vache is not for sale, not in bulk not in retail,” they chanted. Soon a group of paramilitaries appeared, who began to attack the people in advance of their protests. On the evening of February 8, 2014, for example, police beat up Charles Laguerre, Bertin Similien, Lethe Feguens, and Maxo Bell and forced them to remove the barricades they had erected for their protest; they also beat up a young woman, Rosena Masena, merely for walking in the area of Madame Bernard.

The protests have caused several of the companies for the tourism-development project to leave the island. On the other hand, the campaign to persecute the residents, especially the KOPI leaders has gone into full swing. On Thursday February 20, 2014 over 100 heavily-armed police from the Motorized Intervention Brigade (BIM) invaded a school and destroyed several houses. The following day, a government delegation inaugurated a new community center, restaurant and radio station even as people protested and KOPI’s Vice President (a well-known policeman on the island) Jean Matulnès Lamy was arrested.

On Tuesday February 25, 2014, despite a heavy rain, a spontaneous protest broke out when the islanders learned that Matulnès Lamy had been taken to the national penitentiary without being allowed to see a judge. A group of BIM policemen arrived at the protest, along with the local interim governor Fritz Cesar, who singled out the KOPI members for arrest. Live ammunition was fired into the crowd to break up the protest; two people were arrested and 12 were injured.

Residents are outraged by the violence that the government has brought to a bucolic agricultural island that had traditionally needed only two policemen. Children can no longer go to school because of the invasion of their school by heavily-armed police. KOPI members have gone underground and say they are being called “bandits” and accused of poisoning people’s minds.

Seventeen Haitian organizations have signed a communique to demand the release of Jean Matulnès Lamy, and pledged solidarity with the Ile à Vache residents. “We, the signatory organizations bring our solidarity to the struggle of the people of Ile a Vache to stop the island from being turned into a zone for tourism, and we denounce the arrest and imprisonment [without trial] of Jean Matulnès Lamy for having supported the mobilization of the people of the island. We denounce the attacks and other arrests by police to intimidate the population. We believe that these actions against the Ile a Vache population fit in with the logic of macoute power, at the service of the international, that does not respect the principle of the right to self preservation, which is a fundamental democratic principle.”

Senate Committee for Justice and Security Chairman, Pierre Francky Exius has qualified the arrest of Mr. Jean Matulnès Lamy as being politically motivated. Senator Exius announced on February 27, 2014 that he will call on Justice Minister Jean-Renel Sanon and the Chief of Police to discuss the Ile à Vache situation.

As Haitian businessman Antoine Izmery remarked in 1993, during a similar administration when Haiti was run by a US-controlled military junta: “This country is so corrupt that the Americans do not have to do the corruption. They let you steal your own country, just giving you a little protection.” Haitian culture and agriculture are being dismantled, not by foreign interests this time, but by corrupt Haitians, with a nod and a wink from their foreign handlers.

The people of Ile a Vache do not recognize the May 10, 2013 government decree that wants to divest them of their lands and declare the entire island a zone of public utility. KOPI President Marc Lainé Donald (Jinal) said: “This is a lousy decree. This project reflects a macabre plan, a rat trap, a collective suicide, that aims to drive all the residents from the island. It is a cultural genocide that puts everyone in the island’s storm and dispossesses people of their lands. No one has the right to build on the island any more. If Ile à Vache is a hidden treasure, its people should enjoy it and get integrated into the proposed developments. We are craftsmen who have worked to beautify this corner of paradise that is so coveted by Lamothe’s administration.”

Ile a Vache residents call on people everywhere, especially Haitians on the mainland and the diaspora, to support their struggle. They caution everyone to remember the proverb: “When chicken passes by and sees turkey being feathered, chicken should check if it is wet.”

Editor’s Notes: For frequent updates on this story, click here. Photographs two, three, four, six, eight, ten, twelve, fourteen and fifteen by Marie Chantalle. Photographs one, five, seven, nine, eleven and thirteen, and radio reporting in Kreyol by Radyo VKM, Vwa Klodi Mizo.

It is extremely disturbing.